In the Treatment of Diabetes, Success Often Does Not Pay

By IAN URBINA Published: January 11, 2006With much optimism, Beth Israel Medical Center in Manhattan opened its new diabetes center in March 1999. Miss America, Nicole Johnson Baker, herself a diabetic, showed up for promotional pictures, wearing her insulin pump.

In one photo, she posed with a man dressed as a giant foot - a comical if dark reminder of the roughly 2,000 largely avoidable diabetes-related amputations in New York City each year. Doctors, alarmed by the cost and rapid growth of the disease, were getting serious.

At four hospitals across the city, they set up centers that featured a new model of treatment. They would be boot camps for diabetics, who struggle daily to reduce the sugar levels in their blood. The centers would teach them to check those levels, count calories and exercise with discipline, while undergoing prolonged monitoring by teams of specialists.

But seven years later, even as the number of New Yorkers with Type 2 diabetes has nearly doubled, three of the four centers, including Beth Israel's, have closed.

They did not shut down because they had failed their patients. They closed because they had failed to make money. They were victims of the byzantine world of American health care, in which the real profit is made not by controlling chronic diseases like diabetes but by treating their many complications.

Insurers, for example, will often refuse to pay $150 for a diabetic to see a podiatrist, who can help prevent foot ailments associated with the disease. Nearly all of them, though, cover amputations, which typically cost more than $30,000.

Patients have trouble securing a reimbursement for a $75 visit to the nutritionist who counsels them on controlling their diabetes. Insurers do not balk, however, at paying $315 for a single session of dialysis, which treats one of the disease's serious complications.

Not surprising, as the epidemic of Type 2 diabetes has grown, more than 100 dialysis centers have opened in the city.

"It's almost as though the system encourages people to get sick and then people get paid to treat them," said Dr. Matthew E. Fink, a former president of Beth Israel.

Ten months after the hospital's center was founded, it had hemorrhaged more than $1.1 million. And the hospital gave its director, Dr. Gerald Bernstein, three and a half months to direct its patients elsewhere.

The center's demise, its founders and other experts say, is evidence of a medical system so focused on acute illnesses that it is struggling to respond to diabetes, a chronic disease that looms as the largest health crisis facing the city.

America's high-tech, pharmaceutical-driven system may excel at treating serious short-term illnesses like coronary blockages, experts say, but it is flailing when it comes to Type 2 diabetes, a condition that builds over time and cannot be solved by surgery or a few weeks of taking pills.

Type 2 , the subject of this series, has been linked to obesity and inactivity, as well as to heredity. (Type 1, which comprises only 5 percent to 10 percent of cases, is not associated with behavior, and is believed to stem almost entirely from genetic factors.)

Instead of receiving comprehensive treatment, New York's Type 2 diabetics often suffer under substandard care.

They do not test their blood as often as they should because they cannot afford the equipment. Patients wait months to see endocrinologists - who provide critical diabetes care - because lower pay has drawn too few doctors to the specialty. And insurers limit diabetes benefits for fear they will draw the sickest, most expensive patients to their rolls.

Dr. Diana K. Berger, who directs the diabetes prevention program for the City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, said the bias against effective care for chronic illnesses could be seen in the new popularity of another high-profit quick fix: bariatric surgery, which shrinks stomach size and has been shown to be effective at helping to control diabetes.

"If a hospital charges, and can get reimbursed by insurance, $50,000 for a bariatric surgery that takes just 40 minutes," she said, "or it can get reimbursed $20 for the same amount of time spent with a nutritionist, where do you think priorities will be?"

Calorie by calorie, the staff of Beth Israel's center tried to turn diabetic lives around from their base of operations: a classroom and three adjoining offices on the seventh floor of Fierman Hall, a hospital building on East 17th Street.The stark, white-walled classroom did not look like much. But it was functional and clean and several times a week, a dozen or so people would crowd around a rectangular table that was meant for eight, listening attentively, staff members said.

Claudia Slavin, the center's dietitian, remembers asking the patients to stand, one by one.

"Tell me what your waking blood sugar was," she told them, "and then try to explain why it is high or low."

People whose sugars soar damage themselves irreparably, even if the consequences are not felt for 10 or 20 years. Unchecked, diabetes can lead to kidney failure, blindness, heart disease, amputations - a challenging slate for any single physician with a busy caseload to manage.

One patient, Ella M. Hammond, a retired school administrator, recalled standing up in the classroom one day in 1999.

"Has anyone noticed what's different about me?" Ms. Hammond asked.

Blank stares.

"Now, come on," she said, ruffling the fabric of a black gabardine pantsuit she had not worn since slimmer days, years earlier.

"Don't y'all notice 20 pounds when it goes away?" she asked.

Ms. Slavin, one of four full-time staff members who worked at the center, remembers laughing. There were worse reasons for an interruption than a success story.

Like many Type 2 diabetics, Ms. Hammond had been warned repeatedly by her primary care doctor that her weight was too high, her lifestyle too inactive and her diet too rich. And then she had been shown the door, until her next appointment a year later.

"The center was a totally different experience," Ms. Hammond said. "What they did worked because they taught me how to deal with the disease, and then they forced me to do it."

Two hours a day, twice a week for five weeks, Ms. Hammond learned how to manage her disease. How the pancreas works to create insulin, a hormone needed to process sugar. Why it is important to leave four hours between meals so insulin can finish breaking down the sugar. She counted the grams of carbohydrates in a bag of Ruffles salt and vinegar potato chips, her favorite, and traded vegetarian recipes.

After ignoring her condition for 20 years, Ms. Hammond, 63, began to ride a bicycle twice a week and mastered a special sauce, "more garlic than butter," that made asparagus palatable.

She also learned how to decipher the reading on her A1c test, a periodic blood-sugar measurement that is a crucial yardstick of whether a person's diabetes is under control.

"I was just happy to finally know what that number really meant," she said.

Many doctors who treat diabetics say they have long been frustrated because they feel they are struggling single-handedly to reverse a disease with the gale force of popular culture behind it.

Type 2 diabetes grows hand in glove with obesity, and America is becoming fatter. Undoubtedly, many of these diabetics are often their own worst enemies. Some do not exercise. Others view salad as a foreign substance and, like smokers, often see complications as a distant threat.

To fix Type 2 diabetes, experts agree, you have to fix people. Change lifestyles. Adjust thinking. Get diabetics to give up sweets and prick their fingers to test their blood several times a day.

It is a tall order for the primary care doctors who are the sole health care providers for 90 percent of diabetics.

Too tall, many doctors say. When office visits typically last as little as eight minutes, doctors say there is no time to retool patients so they can adopt an entirely new approach to food and life.

"Think of it this way," said Dr. Berger. "An average person spends less than .03 percent of their entire life meeting with a clinician. The rest of the time they're being bombarded with all the societal influences that make this disease so common."

As a result, primary care doctors often have a fatalistic attitude about controlling the disease. They monitor patients less closely than specialists, studies show.

For those under specialty care, there is often little coordination of treatment, and patients end up Ping-Ponging between their appointments with little sense of their prognosis or of how to take control of their condition.

Consequently, ignorance prevails. Of 12,000 obese people in a 1999 federal study, more than half said they were never told to curb their weight.

Fewer than 40 percent of those with newly diagnosed diabetes receive any follow-up, according to another study. In New York City, officials say, nearly 9 out of 10 diabetics do not know their A1c scores, that most fundamental of statistics.

In fact, without symptoms or pain, most Type 2 diabetics find it hard to believe they are truly sick until it is too late to avoid the complications that can overwhelm them. The city comptroller recently found that even in neighborhoods with accessible and adequate health care, most diabetics suffer serious complications that could have been prevented.

This grim reality persuaded hospital officials in the 1990's to try something different. The new centers would provide the tricks for changing behavior and the methods of tracking complications that were lacking from most care.

Instead of having rushed conversations with harried primary care physicians, patients would discuss their weights and habits for months with a team of diabetes educators, and have their conditions tracked by a panel of endocrinologists, ophthalmologists and podiatrists.

"The entire country was watching," said Dr. Bernstein, director of the Beth Israel center, who was then president of the American Diabetes Association.

By all apparent measures, the aggressive strategy worked. Five months into the program, more than 60 percent of the center's patients who were tested had their blood sugar under control. Close to half the patients who were measured had already lost weight. Competing hospitals directed patients to the program.

"For the first time in my 23 years of diabetes work I felt like we had momentum," said Jane Seley, the center's nurse practitioner. "And it wasn't backwards momentum."

Failure for Profit

From the outset, everyone knew diabetes centers were financially risky ventures. That is why Beth Israel took a distinctive approach before sinking $1.5 million into its plan.

Instead of being top-heavy with endocrinologists, who are expensive specialists, Beth Israel relied more on nutritionists and diabetes educators with lower salaries, said Dr. Fink, the hospital's former president.

The other centers that opened took similar precautions.

The St. Luke's-Joslin diabetes center, on the Upper West Side, tried lowering doctors' salaries, hiring dietitians only part time and being aggressive about getting reimbursed by insurers, said Dr. Xavier Pi-Sunyer, who ran the center.

Mount Sinai Hospital's diabetes center hired an accounting firm to calculate just how many bypass surgeries, kidney transplants and other profitable procedures the center would have to send to the hospital to offset the cost of keeping the center running, said Dr. Andrew Drexler, the center's director.

Nonetheless, both of these centers closed for financial reasons within five years of opening.

In hindsight, the financial flaws were hardly mysterious, experts say. Chronic care is simply not as profitable as acute care because insurers, and consumers, do not want to pay as much for care that is not urgent, according to Dr. Arnold Milstein, medical director of the Pacific Business Group on Health.

By the time a situation is acute, when dialysis and amputations are necessary, the insurer, which has been gambling on never being asked to cover procedures that far down the road, has little choice but to cover them, if only to avoid lawsuits, analysts said.

Patients are also more inclined to pay high prices when severe health consequences are imminent. When the danger is distant, perhaps uncertain, as with chronic conditions, there is less willingness to pay, which undercuts prices and profits, Dr. Milstein explained.

"There is a lesser sense of alarm associated with slow-moving threats, so prices and profits for chronic and preventive care remain low," he said. "Doctors, insurers and hospitals can command much higher prices and profit margins for a bypass surgery that a patient needs today than they can for nutrition counseling likely to prevent a bypass tomorrow."

Ms. Seley said the belief was that however marginal the centers might be financially, they would bring in business.

"Diabetes centers are for hospitals what discounted two-liter bottles of Coke are to grocery stores," she said. "They are not profitable but they're sold to get dedicated customers, and with the hospitals the hope is to get customers who will come back for the big moneymaking surgeries."

Indeed, former officials of the Beth Israel center said they anticipated that operating costs would be underwritten by the amputations and dialysis that some of their diabetic patients would end up needing anyway, despite the center's best efforts. "In other words, our financial success in part depended on our medical failure," Ms. Slavin said.

The other option was to have a Russ Berrie.

Mr. Berrie, a toymaker from the Bronx, made a fortune in the 1980's through the wild popularity of a product he sold, the Troll doll, a three-inch plastic monster with a puff of fluorescent hair. Mr. Berrie took more than $20 million of his doll money and used it to finance the diabetes center at Columbia University Medical Center in memory of his mother, Naomi, who had died of the disease. The center was also helped by a million-dollar grant from a company that makes diabetes drugs and equipment.

Even with its stable of generous donors, even with more than 10,000 patients filing through the doors each year, the Columbia center struggles financially, said Dr. Robin Goland, a co-director. That, she said, is because the center runs a deficit of at least $50 for each patient it sees.

Without wealthy benefactors, Beth Israel's center had an even tougher time surviving its financial strains.

Ms. Slavin said the center often scheduled patients for multiple visits with doctors and educators on the same day because it needed to take advantage of the limited time it had with its patients. But every time a Medicaid patient went to a diabetes education class, and then saw a specialist, the center lost money, she said. Medicaid, the government insurance program for the poor, will pay for only one service a day under its rules.

The center also lost money, its former staff members said, every time a nurse called a patient at home to check on his diet or contacted a physician to relate a patient's progress. Both calls are considered essential to getting people to change their habits. But medical professionals, unlike lawyers and accountants, cannot bill for phone time, so more money was lost.

And the insurance reimbursement for an hourlong diabetes class did not come close to covering the cost. Most insurers paid less than $25 for a class, said Denise Rivera, the secretary for the center.

"That wasn't even enough to pay for what it cost to have me to do the paperwork to get the reimbursement," she said.

Beth Israel was not alone in this predicament. Dr. C. Ronald Kahn, president and director of the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston, the nation's largest such center, with 23 affiliates around the country, said that for every dollar spent on care, the Joslin centers lost 35 cents. They close the gap, but just barely, with philanthropy, he said.

"So you have the institutions, which are doing much of the work in dealing with this major health epidemic, depending on charity," he said. "In the long run, this is definitely not a tenable system."

Plastic Strips and Red Tape

Sidney Schonfeld was not a patient at Beth Israel, but he ran into his own set of financial obstacles in trying to manage his disease.

"Controlling my condition isn't that hard," said Mr. Schonfeld, 82, a retired businessman from Washington Heights. "The hard part are the things outside my control, like getting the test strips and the medicines."

Test strips are not complicated pieces of medical equipment. They are inch-long pieces of plastic with tiny metal tabs that diabetics use to measure the sugar in their blood. After pricking their finger, diabetics place a drop of blood on the strip and then insert it into the side of a handheld meter that analyzes their sugar levels.

Each strip costs only about 75 cents, but many diabetics are poor and, over the course of a year, those who test their blood frequently, as instructed, will spend more than $500 on strips.

Mr. Schonfeld, like many diabetics, is supposed to test his blood at least twice a day so he can make adjustments to his diet and medications that can ward off serious complications. But many insurers cover only one strip per day unless a patient obtains written justification from a doctor. Even with letters from his doctor, Mr. Schonfeld has had a tough time getting insurers to pay for his strips, his doctor and nurse said."Fighting the disease is only half of this job," said Mr. Schonfeld's doctor, Dr. Goland. She held up a manila folder thick with letters that she had sent to his insurer explaining Mr. Schonfeld's case. Mr. Schonfeld had his own pile of letters: the rejection notices he got back.

Dr. Goland says that Mr. Schonfeld has good reason to be vigilant. His mother lost her left foot to Type 2 diabetes. She died several months later after gangrene spread to her right. Mr. Schonfeld's six uncles and aunts on his mother's side had the disease. Three of them underwent amputations. His son, Gary, is also diabetic.

"You can't get a more textbook high-risk case than Sidney," Dr. Goland said.

Though the health care system asks diabetics to become rigorously involved in daily management of their conditions, red tape and the cost of drugs and supplies put self-management out of reach for many patients. As a result, many diabetics either do without or pay out of their own pockets. Some resort to other means to get their supplies.

In Indiana, hospital workers organized Diabetes Bingo Night last May to collect money for strips and supplies. In California, F.B.I agents found that diabetics were buying stolen strips on eBay. Last year, the agents charged a couple with mail fraud and accused them of having sold $2.5 million worth of stolen test strips and supplies.

In East Harlem, doctors at Mount Sinai were mystified by a number of cases in 2002: patients came into the hospital asserting that they had been testing themselves daily and were sure that their blood sugar was under control. Hospital tests, however, showed just the opposite.

"We finally figured out," said Dr. Carol R. Horowitz, an assistant professor at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, "that patients who could not afford the strips for their blood monitor were buying cheaper strips that were incompatible and that were giving false reads."

At least they knew they had the disease. A third of diabetics do not, in part because doctors do not screen as often as they should, studies show. Since symptoms do not appear for 7 to 10 years on average, the effects of the elevated sugars begin to build and become irreversible.

Mr. Schonfeld has known about his diabetes for more than 20 years and prides himself on keeping it in check.

"I've seen what it can do," he said. "So I know better than to ignore it."

When Dr. Goland told him to limit the chocolate mousse and frankfurters, he did.

When she told him to start walking two miles a day, he did that, too. But her instructions to test his blood at least twice a day were not as easy to follow.

Mr. Schonfeld runs out of strips even though he tries to plan ahead by ordering extras, said Kathy Person, his nurse. "The insurance reps say they don't want the strips to end up on the black market, so they don't let people preorder extras," she said.

The Naomi Berrie Diabetes Center has a full-time staff member who tries to do the clerical work associated with insurance coverage. "Still, it's a struggle to keep up with the paperwork," Dr. Goland said.

Some doctors simply do not have time and patients are left to haggle with insurers - usually unsuccessfully - on their own.

Although a recent federal study found that an increasing number of health insurers cover strips, few cover more than one a day, according to strip manufacturers. In fact, a study last year by Georgetown University found that insurance restrictions on strips and other services for diabetics were reducing the quality of care.

"I was a businessman for more than 40 years," said Mr. Schonfeld, a former food importer. "What I just don't understand is how these insurance companies can operate the way they do and keep their customers."

Sick Patient? Expensive Patient

As it turns out, keeping customers who are diabetic is not the goal of most health insurance companies, experts said. Avoiding diabetics is actually more the point.

Understanding why, the experts said, requires an appreciation of one of the crucial obstacles to better diabetes care.

Most insurers do not operate the way Mr. Schonfeld did in the import business, luring additional customers by advertising a good product at a fair price. Were they to operate in that fashion, health plans looking to grow might advertise better coverage for diabetics, such as a wide choice of blood-sugar monitors.But in the insurance business - and virtually all businesses based on risk - the point is not to attract the most customers but rather the best ones. As businesses, not charities, insurers need to attract healthy customers, not sick ones, said David Knutson, a former insurance executive who studies the industry's economics for the Park Nicollet Institute, a health research organization in Minneapolis.

As a result, experts say, insurance executives usually think twice before bolstering their diabetes benefits, for fear they will attract the chronically ill.

In a 2003 survey, 87 percent of health insurance actuaries queried by Mr. Knutson said that if they were to improve coverage with richer drug benefits or easier access to specialists, they would incur financial problems by attracting the sickest, most expensive patients.

"Insurers are as eager to attract the chronically ill as banks are interested in loaning to the unemployed," Mr. Knutson said. "The chances of losing money are simply too high."

Insurers are not alone in these concerns. Large employers, many of which devise and finance their own employee health plans, know that their allotted reserves are jeopardized if too much of their work force is seriously ill. Last year, for example, a Wal-Mart executive suggested in an internal memo that the company could reduce costs by discouraging unhealthy people from applying for work.

Even when insurers are simply third-party administrators, processing claims but not covering the actual medical expenses, they try to keep claims down by attracting healthier patients to their plans, Mr. Knutson said.

Similarly, coverage for Medicaid recipients, though underwritten by the government, can be subject to the same private-sector pressures. More than 70 percent of Medicaid recipients in New York now receive their health care through private health maintenance organizations that operate under government contract. These H.M.O.'s get the same annual flat fee from the government, regardless of whether the patient is robustly healthy or chronically ill, thus creating an incentive to attract the healthiest customers.

For insurers, the high cost of attracting the sick is far from a hypothetical problem, said David V. Axene, president of Axene Health Partners, a consulting firm that advises these companies. For each additional session of nutritional counseling, he said, an insurer must account for the likely cost of luring sick patients away from its competitors.

Mr. Axene cited an example from several years ago when, he said, an insurer became puzzled about why a provider network that it had set up at a Boston hospital was consistently over budget. Mr. Axene's company found that two-thirds of the hospital's diabetics had chosen to enroll in that network over others.

The reason? The insurer had mistakenly listed an endocrinologist on its network's primary care physician list, he said.

"These patients no longer needed to get a referral to see the endocrinologist, and with one visit they could get their general and their diabetes needs filled," Mr. Axene said. Within months, the network had redrafted its lists, dropping the endocrinologist, he said.

Mohit Ghose, a spokesman for America's Health Insurance Plans, an industry trade association, said insurers were working to improve chronic care coverage. Many have created disease management programs to track their sickest patients and pay bonuses to doctors who show results in treating the chronically ill.

"Is there still a long way to go? Yes, definitely," Mr. Ghose said. "But we're on the right track."

Some preventive measures would, at first glance, seem sure money savers for health insurers since they might eliminate or forestall expensive diabetes complications down the road. But many insurers do not think that way. They figure that complications are often so far into the future, insurance analysts say, that many people will have already switched jobs or insurers, or have even died, by the time they hit. As a result, any savings from preventive measures will only go to their competitors anyway, analysts say.

In fact, experts say, people generally change their health insurance about every six years.

"It's perverse," Mr. Knutson said. "But it's the reality of there being a weak business case for quality when it comes to handling chronic care."

'Jerry, We Need to Talk'

It usually took Dr. Bernstein seven minutes to walk from his office in Fierman Hall to the hospital president's office across 17th Street. On Jan. 4, 2000, he had a bounce in his step, and it took him half that time, he recalled.He had a good story to tell, and graphs and tables to back it up. The Beth Israel center was an unqualified medical success. In fact, patient loads were growing by 20 percent each month as its reputation spread.

When he arrived, Dr. Fink, then the hospital's president, asked the three other executives to take their seats. Dr. Bernstein began talking before he had reached his chair.

"Things are really coming along well," he said as he handed out a spreadsheet. "Patients are starting to turn their lives around."

Pausing, Dr. Bernstein looked around the table. He was struck by an awkward silence.

"Jerry, we need to talk about what is happening at the hospital," Dr. Fink said. "We're going to have to close your program."

Dr. Bernstein cannot say which was more jarring: the news or the way it arrived.

Numb, he kept his composure for 25 minutes, he said. The administrators explained that the hospital was running a deficit. The diabetes program was not helping matters.

"It was really not about the medicine but the business," Dr. Fink said recently about the meeting. "That didn't make it any easier to deliver the news, especially since I had been one of the main advocates behind getting the center started."

After the meeting, as Dr. Bernstein walked back to his office, he wondered where he would direct the program's 300 or so patients. Still, he remained sympathetic to the hospital's plight.

"I was not of the belief that we should save the center only to end up losing the hospital," he said.

For many of the patients, the news was a second strike of lightning. They had come to Dr. Bernstein only after being cut loose by the closing of the St Luke's diabetes center earlier that year. Now they were being cut loose again, to drift back to a life of limited care options: understaffed and overwhelmed clinics; general practitioners with too little time; a city with about 100 overbooked diabetes educators surrounded by 800,000 patients; and a shortage of endocrinologists, the specialists who are often critical providers of diabetes care.

Since endocrinology is one of the lower-paying specialties, there is a national shortage of such doctors. In New York, with its armies of diabetics, patients must often wait months for an appointment with one of fewer than 200 endocrinologists. The poorest patients face the biggest problem, as only a fraction of the specialists accept Medicaid.

Once the center had closed, Dr. Bernstein continued to teach at Beth Israel, but he began to devote more and more time to a side project. He was working on an inhaler that delivers insulin in the form of a mist. The product is being developed by Generex, and it is designed to appeal to patients who are reluctant to use insulin because they do not like the idea of injections or needles.

But the device will probably cost about 15 percent more than traditional insulin and is likely to be too expensive for many of the poorest diabetics, who are often the patients who need it most because their illness is most severe.

"The center was a way to really make a dent in this epidemic," Dr. Bernstein said. "The inhaler is a promising breakthrough. But it's mostly a business opportunity."

Other pharmaceutical innovations are likely to soften the toll of diabetes for many patients in coming years, doctors said. With an average diabetic spending more than $2,500 per year on drugs and equipment, pharmaceutical companies have good reason to focus their attention on the more than $10 billion market in controlling the disease's complications.

But there is only so much the drugs can do, they add, if they are not accompanied by the sort of changes in patient habits that the centers fostered through education and monitoring.

Health economists suggest that if these preventive measures were practiced on a wide scale, complications from diabetes would be largely eliminated and the American medical system, and by extension taxpayers, could save as much as $30 billion over 10 years. The experts disagree on what such an effort would cost. (How much nutrition counseling does it take to wean the average person from French fries?) Nonetheless, many of them believe the cost would be largely offset by the savings.

Dr. Bernstein says the lone hope on the horizon is a restructured reimbursement system that puts the business of chronic care on a more competitive footing with acute care. Experts say this restructuring could start if government insurance programs like Medicaid began paying more for preventive efforts like education, a move that the private sector would be likely to follow."Until we address the financing and the reimbursement structure, this disease is going to rage out of control," Dr. Bernstein said.

Not everyone believes the centers were the best answer to diabetes care. Even with their demise, many hospitals, clinics and endocrinology practices say they are providing cost-effective, quality treatment.

"The care we provide now is on the par with what was offered before," said Dr. Leonid Poretsky, who became director of Beth Israel's endocrinology division after the diabetes program closed. "The main difference is that we are financially viable because half of our patients are not diabetic."

These facilities, though, often find themselves in the same position the centers did: financing prevention efforts with profits from the very kidney transplants and amputations that preventive care is meant to deter.

It is tough to convince a former patient like Ms. Hammond that the closing of the Beth Israel center was anything but a mistake. She had started to make critical changes in her lifestyle after just a few weeks there. She did not find out it had closed, she said, until several months after the doors had shut, when she called looking to sign up for a refresher class. She was starting to fall back into old habits.

"I needed reminding," she said.

With the center gone, Ms. Hammond said she has had to try to muddle through. She goes to the podiatrist once a year, but she said she could not remember the last time she visited an eye doctor. She has gained about 40 pounds.

Some days she wakes up and her blood sugar is high. Other mornings she doesn't bother to check, she said.

"I couldn't get to where I was before," she said.

Two years ago, she said, she took a last look at that favorite gabardine pantsuit she had once modeled for her class. Then, she said, she gave it to her cousin.

About the Author:

Thomas Smith is a reluctant medical investigator, having been forced into curing his own diabetes because it was obvious that his doctor would not or could not cure it.

He has published the results of his successful diabetes investigation in his self-help manual, Insulin: Our Silent Killer, written for the layperson but also widely valued by the medical practitioner. This manual details the steps required to reverse Type II diabetes and references the work being done with Type I diabetes. The book may be purchased from the author at PO Box 7685, Loveland, Colorado 80537, USA (North American residents send $US25.00; overseas residents should contact the author for payment and shipping instructions).

Thomas Smith has also posted a great deal of useful information about diabetes on his website, https://www.Healingmatters. com. He can be contacted by telephone at +1 (970) 669 9176 and by email at valley@healingmatters.com.

Endnotes:

1. National Center for Health Statistics, "Fast Stats", Deaths/Mortality Preliminary 2001 data

2. Dr Herbert Ley, in response to a question from Senator Edward Long about the FDA during US Senate hearings in 1965

3. Eisenberg, David M., MD, "Credentialing complementary and alternative medical providers", Annals of Internal Medicine 137(12):968 (December 17, 2002)

4. American Diabetes Association and the American Dietetic Association, The Official Pocket Guide to Diabetic Exchanges (

), McGraw-Hill/Contemporary Distributed Products, newly updated March 1, 1998

5. American Heart Association, "How Do I Follow a Healthy Diet?", American Heart Association

National Center (7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, Texas 75231-4596, USA), https://www.americanheart.org

6. Brown., J.A.C., Pears Medical Encyclopedia Illustrated, 1971, p. 250

7. Joslyn, E.P., Dublin, L.I., Marks, H.H., "Studies on Diabetes Mellitus", American Journal of

Medical Sciences 186:753-773 (1933)

8. "Diabetes Mellitus", Encyclopedia Americana, Library Edition, vol. 9, 1966, pp. 54-56

9. American Heart Association, "Stroke (Brain Attack)", August 28, 1998, https://www.amhrt.org;

American Heart Association, "Cardiovascular Disease Statistics", August 28, 1998,

https://www.amhrt.org/;

"Statistics related to overweight and obesity",

https://niddk.nih.gov/;

https://www.winltdusa.com/

10. "Diabetes Mellitus", Encyclopedia Americana, ibid., pp. 54-55

11. The Veterans Administration Coronary Artery Bypass Co-operative Study Group, "Eleven-year survival in the Veterans Administration randomized trial of coronary bypass surgery for stable angina", New Eng. J. Med. 311:1333-1339 (1984); Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS), "A randomized trial of coronary artery bypass surgery: quality of life in patients randomly assigned to treatment groups", Circulation 68(5):951-960 (1983)

12. Trager, J., The Food Chronology, Henry Holt & Company, New York, 1995 (items listed by date)

13. "Margarine", Encyclopedia Americana, Library Edition, vol. 9, 1966, pp. 279-280

14. Fallon, S., Connolly, P., Enig, M.C., Nourishing Traditions, Promotion Publishing, 1995;

Enig, M.C., "Coconut: In Support of Good Health in the 21st Century", https://www.livecoconutoil.com/maryenig.htm

15. Houssay, Bernardo, A., MD, et al., Human Physiology, McGraw-Hill Book

Company, 1955, pp. 400-421

16. Gustavson, J., et al., "Insulin-stimulated glucose uptake involves the transition of glucose transporters to a caveolae-rich fraction within the plasma cell membrane: implications for type II diabetes", Mol. Med. 2(3):367-372 (May 1996)

17. Ganong, William F., MD, Review of Medical Physiology, 19th edition, 1999, p. 9, pp. 26-33

18. Pan, D.A. et al., "Skeletal muscle membrane lipid composition is related to adiposity and insulin action", J. Clin. Invest. 96(6):2802-2808 (December 1995)

19. Physicians' Desk Reference, 53rd edition, 1999

20. Smith, Thomas, Insulin: Our Silent Killer, Thomas Smith, Loveland, Colorado, revised 2nd edition, July 2000, p. 20

21. Law Offices of Charles H. Johnson & Associates (telephone 1 800 535 5727, toll free in North America)

22. American Heart Association, "Diabetes Mellitus Statistics", https://www.amhrt.org

23. Shanmugasundaram, E.R.B. et al. (Dr Ambedkar Institute of Diabetes, Kilpauk Medical College Hospital, Madras, India), "Possible regeneration of the Islets of Langerhans in Streptozotocin-diabetic rats given Gymnema sylvestre leaf extract", J. Ethnopharmacology 30:265-279 (1990);

Shanmugasundaram, E.R.B. et al., "Use of Gemnema sylvestre leaf extract in the control of blood glucose in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus", J. Ethnopharmacology 30:281-294

(1990)

24. Smith, ibid., pp. 97-123

25. Many popular artificial sweeteners on sale in the supermarket are extremely poisonous and dangerous to the diabetic; indeed, many of them are worse than the sugar the diabetic is trying to avoid; see, for example, Smith, ibid., pp. 53-58.

26. Walker, Morton, MD, and Shah, Hitendra, MD, Chelation Therapy

27. Expensive but Delicious ~ A little goes a long way: May this website author also suggest Gourmet Virgin Tea Oil?

28. Your source for research on the health benefits of coconut

oil: https://www.coconutoil.com/

29. Virgin Coconut Oil: The Healthy Oil for Diabetes by Bruce Fife, N.D.

(

), Keats Publishing, Inc., New Canaan, Connecticut, 1997, ISBN 0-87983-730-6

Fats and Oils

Fats and oils are an important part of any well designed dietary plan. A good working understanding of just what they are and how they work is an essential part of any well conceived diet. Fats and oils, certainly as much and perhaps more than any other single dietary component, directly impact our health in profound ways.

The difference between fats and oils is in their melting point. Fats tend to be solids at room temperature; oils tend to be liquid at room temperature. To turn a fat into an oil, merely raise its temperature above its melting point. If the temperature continues to increase beyond the melting point to the point where some smoke becomes evident, the molecular structure of the oils will change and a number of toxic molecular isomers will be produced in the oil. If the oil is allowed to cool or to resolidify, the toxic products will remain. The temperatures where this damage is done to our fats and oils is about half the temperatures reached in the refining and Hydrogenation processes (part of the aforementioned "" of greed). Thus, these processes routinely destroy all of the nutritional value of our fats and oils. These refined and/or Hydrogenated fats and oils are characterized by an extraordinarily long shelf life; some are virtually un spoilable (e.g. "vegetable" oil, "canola" {a.k.a. oilseed or lear} oil, "safflower" oil, peanut oil, etc...).

Naturally occurring fats and oils are Triglycerides. Triglycerides consist of three fatty acids bound to a Glycerol backbone. Each fatty acid consists of a Carbon-Hydrogen chain with a Carboxyl group at the end that is attached to the Glycerol molecule. The other end is typically terminated with a Hydrogen bond. Unless changed chemically, by artificial technology, this is the natural form which we find in the fats and oils that are nutritionally useful. The length of the fatty acid chain as well as its configuration and relative degree of saturation determine how the fatty acid will act within our body. Some fatty acids are vitally necessary to life processes; some are poisons.

Naturally occurring fats and oils are Triglycerides. Triglycerides consist of three fatty acids bound to a Glycerol backbone. Each fatty acid consists of a Carbon-Hydrogen chain with a Carboxyl group at the end that is attached to the Glycerol molecule. The other end is typically terminated with a Hydrogen bond. Unless changed chemically, by artificial technology, this is the natural form which we find in the fats and oils that are nutritionally useful. The length of the fatty acid chain as well as its configuration and relative degree of saturation determine how the fatty acid will act within our body. Some fatty acids are vitally necessary to life processes; some are poisons.

Fatty acids are also found in other molecules besides Triglycerides. For example Phospholipids have two fatty acids and a Phosphorus molecule attached to the Glycerol backbone. Phospholipids too, play an important role in our cellular health.

Fatty acids are also found in other molecules besides Triglycerides. For example Phospholipids have two fatty acids and a Phosphorus molecule attached to the Glycerol backbone. Phospholipids too, play an important role in our cellular health.

Understanding Triglycerides is an important issue that is complicated by a great deal of pseudo science that is specifically designed to confuse and mislead. In addition to the Triglycerides that we eat in the form of fats and oils, we also have Triglycerides formed, within our bodies, from the sugars and starches that we eat. Much of this Triglyceride load is deposited in our adipose (fat) cells when we eat too much fat and sugar and some of us become obese. Some of these Triglycerides are broken down into their fatty acids which are then used in cell repair. When we lack CIS type w=3's in our diet, most of the fatty acid load is either trans-fats or saturated fats; these are used to repair our cell membranes. It is the combined absence of the CIS w=3 fats and oils and the presence of these saturated and trans-fats and other toxic isomers that cause these cellular membranes to become stiff and sticky instead of fluid and slippery. Additional biochemical detail on this cellular membrane issue is discussed on the above diabetes article.

The saturated fat Triglycerides circulate in the blood stream before finding a home in our Adipose cells (fat cells). They tend to be sticky instead of slippery and so contribute to the high incidence of Strokes and Atherosclerosis associated with high levels of Triglycerides in the blood. They make the blood viscosity thicker and cause the Platelets to tend to stick together. They are also an essential step in the chain of events that cause obesity.

All dietary fatty acids may be divided into two categories: Saturated and Unsaturated. The Unsaturated fats and oils differ from each other in their configuration and in their degree of unsaturation. Both types of fatty acids are produced by the the animal and by the vegetable kingdoms, although some are predominately found in animal sources and some are predominately found in vegetable sources. Most concentrated vegetable sources are seeds and nuts; most animal sources are animal body fat. Unrefined fish oils are good sources of dietary CIS w=3 fats; unrefined Flax seed oil, Hemp seed oil and several others are good concentrated vegetable sources of CIS w=3 oils (which makes our corporate food system a dictatorship since the big chain grocery stores have summarily removed most of these healthy oils from the shelves).

Saturated fats are characterized by having all of the possible molecular locations for a Hydrogen bond filled. Thus, at the molecular level, there is no molecular difference between a saturated vegetable fat or a saturated animal fat of the same chain length. There also is no molecular difference between a natural and an artificial saturated fat of the same chain length. Configuration is not an issue because when all of the bonds are filled there is only one configuration possible. As the length of the fatty acid chain lengthens the melting point of the fat increases. Thus fats which are solid at room temperature have longer chain lengths than fats which are liquid at room temperatures. Our bodies can readily process short and medium chain fats; but, it processes longer chain fats with greater difficulty.

However, with animal sources, vegetable sources and even with artificially made dietary sources, single individual fat molecules are never found. We must always deal with mixtures of many different fat and oil molecules in the fats and oils that we consume. All naturally occuring fats and oils are mixtures of long and short chain saturated fats and mixtures of mono and poly unsaturated fats of the CIS configuration. Naturally occuring trans-isomers are relatively rare and do not occur in sufficient abundance to create a health hazard. However if fats and oils are refined, heated or Hydrogenated, the mixtures are then made to also include a huge thermodynamic distribution of highly toxic isomers, including the notorious trans-isomer, along with partially destroyed molecular fragments, and other toxic products. (Food products are beginning to be labelled "No Trans Fat!" but we still need to question the possible presence of other toxic substances: Examine the ingredients and ask the manufacturer about suspected oils.)

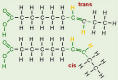

All fats and oils differ from each other in the length of the Carbon-Hydrogen chain; however, unsaturated fats and oils also differ from each other, and from saturated fats, in that they have one or more vacant Hydrogen sites along their chain. These unfilled Hydrogen binding sites give the unsaturated fats and oils a variety of geometries at the molecular level. Some of these geometries, notably the "CIS" geometries that occur naturally in nature and are designed so that our metabolism can readily handle them, in fact, it needs them. Certain CIS type unsaturated oils, the w=3's, directly constitute an important building block in all of the sixty seven or so trillion cells in our body, and they cannot be obtained by our body except from our food supply. In addition, our enzyme systems use unsaturated fats as building blocks to construct a wide variety of needed biochemicals.

Short and medium chain length saturated animal fats are a very nutritious food staple and have been for thousands of years. They provide nine calories per gram and are "good keepers"; in the days before refrigeration, this "keeping" quality was very important. It meant that the fat would not spoil or go rancid easily at room temperature. Our body uses saturated fats as a highly concentrated energy source when carbohydrates not plentiful. Much of the disease we experience today is the result of a failure of our systems to properly and safely metabolize fats and oils (e.g. diabetes). Rather than use them for the highly concentrated energy source that they are, our body uses them in cell repair because the CIS w=3's are not in our diet. This is now identified as a major factor in Hyperinsulinemia.

what ratio of cholesterol does the liver make? Cholesterol is a fatty substance that is manufactured by our liver. It is an extremely important building block for many of our vital functions including our brains, eyes, nervous systems and sexual apparatus (both varieties). About 85% of the Cholesterol circulating in our bodies is made by the liver. We have a Cholesterol control mechanism in our bodies that operates to stabilize Cholesterol at the circulating level that we find. Cholesterol is also contained in some of the foods that we eat. If we try to reduce our circulating Cholesterol by excluding high Cholesterol foods from our diet, our liver simply makes more Cholesterol in an attempt to maintain a homeostasis (normal level) of Cholesterol in our blood stream. Controlling circulating Cholesterol through diet is like trying to empty the ocean with a teaspoon; it sounds like a good pop science theory but it is really not very effective.

Cholesterol is a fatty substance that is manufactured by our liver. It is an extremely important building block for many of our vital functions including our brains, eyes, nervous systems and sexual apparatus (both varieties). About 85% of the Cholesterol circulating in our bodies is made by the liver. We have a Cholesterol control mechanism in our bodies that operates to stabilize Cholesterol at the circulating level that we find. Cholesterol is also contained in some of the foods that we eat. If we try to reduce our circulating Cholesterol by excluding high Cholesterol foods from our diet, our liver simply makes more Cholesterol in an attempt to maintain a homeostasis (normal level) of Cholesterol in our blood stream. Controlling circulating Cholesterol through diet is like trying to empty the ocean with a teaspoon; it sounds like a good pop science theory but it is really not very effective.

Here are important questions we need to ask about cholesterol before we jump on another health trend band wagon:

{While you are reading the following article please notice that the author never attempts to define or even spell out low density lipoprotein, never attempts to explain the purpose of LDLs in the body, never attempts to explain how LDLs are manufactured or regulated in the body, AND never attempts to explain the diet and lifestyle that can throw cholesterol levels off kilter. In essence, this is propaganda because it does not attempt to educate the public, but constantly refers to LDLs as a bad fat although it is manufactured by the liver in every healthy body and this article influences the public to take more statins to make the pharmaceutical companies richer. This Propaganda is most dangerous since it takes a position within respected media such as the NY Times with "experts" backing up the claim to "do the right thing."}

As we shall see elsewhere in this website and in our special report Insulin: Our Silent Killer the best way to reduce Cholesterol levels to normal is to cure the underlying Hyperinsulinemia. This entails repairing the Automatic Cholesterol Control System which regulates our Cholesterol homeostasis. This repair process requires stabilizing our blood Insulin and Glucose levels and restoring our entire endocrine system to proper balance. This follows automatically when we stop consuming dangerous, damaged fats and oils and restore other needed nutrition to our diet.

Cholesterol, being a fat, does not dissolve in the blood stream which is mostly water. In order to be transported around in the blood, it must be carried by a Lipoprotein carrier which has an affinity for water. When it is being carried from the liver to the rest of the body, the Lipoprotein involved is LDL (low density Lipoprotein). When Cholesterol is being carried from the body back to the liver for recycling, the carrier is HDL (high density Lipoprotein). Thus LDL which distributes Cholesterol throughout the body came to be known as the "bad" Cholesterol and HDL which removes it from circulation came to be known as the "good" Cholesterol. Hyperinsulinemia is characterized by a reduction in the HDL fraction and an increase in the LDL fraction. Clearly this sort of phony science that characterizes one essential Lipoprotein as "good" and another as "bad" is the sort that comes from marketing and sales departments; certainly it does not originate in reputable scientific laboratories.

Besides being a most important building block in many of our bodily functions, Cholesterol is one of the important components of the plaque that occludes our arteries. It is for this reason that it has attracted notice. Our diseased state is due to the fact that the normal levels of circulating Cholesterol have been elevated by Hyperinsulinemia. In fact, this elevated level of Cholesterol is often one of the early warning signs that we are becoming Hyperinsulinemic. An appropriate way to reduce Cholesterol is to cure the underlying Hyperinsulinemia.

With the advent of artificial fats and oils and Hydrogenated and Refined products in the 1920's (see history), the CIS type w=3 unsaturated oils started to disappear from our dietary food chain and were replaced by a large number of toxic isomers. These toxic isomers are just different geometries of the unsaturated oil molecules many of which were, before processing, of the CIS type. Long term consumption of some of these toxic isomers, notably the trans-isomer, has been identified with many, if not most, of the chronic disease symptoms discussed on this home page. Of even greater importance, the complete removal of some of the CIS type w=3 oils from our diet has been found to be causal in many of our widespread degenerative diseases including Hyperinsulinemia.

Some of the biochemical effects of these toxic isomers are discussed on the diabetes page.

Much of this came about because of standardized refining processes that were introduced into the oils manufacturing business. The new rapid high temperature extraction techniques, introduced in the 1920's lowered the retail price of oil, gave it a pure pristine appearance when packaged in a transparent bottle, gave it a uniform clarity, gave it an almost uniform taste, and destroyed the CIS w=3 fatty acids that rapidly spoiled at room temperature. It is the high temperatures used in the refining process that ruins even previously good oils. If we find a good oil and refrigerate it, it is still easy to destroy its nutritional qualities when we cook with it by heating it to the point where it smokes. When delicate CIS w=3 oils are over heated, either in cooking or refining, the oil undergoes irreversible changes; the CIS configuration is destroyed and many toxic isomers are generated, including the notorious trans-isomer. All of the antioxidents, previously a part of the unrefined oil are destroyed. Much of the oil's original flavor is lost and it tastes like a generic oil.

Much of this came about because of standardized refining processes that were introduced into the oils manufacturing business. The new rapid high temperature extraction techniques, introduced in the 1920's lowered the retail price of oil, gave it a pure pristine appearance when packaged in a transparent bottle, gave it a uniform clarity, gave it an almost uniform taste, and destroyed the CIS w=3 fatty acids that rapidly spoiled at room temperature. It is the high temperatures used in the refining process that ruins even previously good oils. If we find a good oil and refrigerate it, it is still easy to destroy its nutritional qualities when we cook with it by heating it to the point where it smokes. When delicate CIS w=3 oils are over heated, either in cooking or refining, the oil undergoes irreversible changes; the CIS configuration is destroyed and many toxic isomers are generated, including the notorious trans-isomer. All of the antioxidents, previously a part of the unrefined oil are destroyed. Much of the oil's original flavor is lost and it tastes like a generic oil.

When cooking with fats and oils it is important to do so in a manner that does not destroy them. Use only butter, Organic Virgin Coconut Oiltoxic isomers (Use that deep fryer for boiling and steaming). If you cook with an oil like olive oil, be sure to mix some water with it to prevent the oil from getting too hot. Remember that if the oil starts to smoke it is too hot and it is being

destroyed.

To cure Hyperinsulinemia, Type II Diabetes, Syndrome X and many other consequential diseases that stem from poisonous fats and oils, it is important to realize that the chronic ingestion of Refined and Hydrogenated fats and oils is implicated as a causal agent in these diseases. Margarine, artificial shortenings, refined oils and all Hydrogenated edible products are long term toxic to the human metabolism. Any unsaturated fat or oil that does not need constant refrigeration should be considered un edible. Many saturated fats and oils, while also benefiting from refrigeration, do not turn rancid nearly so easily as CIS w=3 type unsaturated fats and oils at room temperature.

An important consideration about these edible oils is a widespread fraudulent advertising technique that enables the oils manufacturer to sell known toxic oils to the unsuspecting public without breaking the law (in the same way fluoride is marketed by "approval" of certain government "health" agencies). Many refined vegetable oils are advertised as mono unsaturated or as polyunsaturated in order to confuse the purchaser. Indeed, if these oils were the CIS isomer, they would be desirable oils from a health standpoint. However, CIS type w=3 oils are inherently unstable and will go rancid quite rapidly in a transparent bottle on a room temperature grocery store shelf; their shelf life is on the order of ten hours or sometimes less (like milk or eggs). The trans-isomer of these oils has a much longer room temperature shelf life. There is no law to require the oils manufacturer, or the store, to advise the consumer that these "monounsaturates" and "polyunsaturates" are trans-isomers and other toxic byproducts that result from the destruction of the good edible oils that they think they are getting. Since no law exists to keep their claims honest, oils manufacturers feel free to deceive with dishonest claims that few consumers understand. In some circles this is not considered to be fraud. {Update: According to an official response from the American Diabetes Association standardized labeling of food products containing toxic isomers begins in 2006.}

In our discussion on Hyperinsulinemia we discuss more about the fat and oil issue and cover in detail ways we can protect ourselves from the consequences of the fraudulent advertising claims with which we are constantly bombarded. We also discuss how to reverse the degenerative process in the event we are involved with it.

More information is available in our hardcopy Special Report for those who have a compelling interest or who simply wish to know more about the health connection to our dietary fats and oils.

References:

- Erasmus U PhD, "Fats that heal Fats that kill" ( ), Alive Books, 7436 Frazer Park Drive, Burnaby BC, Canada 1996

- Johnston JR PhD, Johnson IM CN, "Flaxseed (Linseed) oil and the power of omega-3," ( ) Keats publishing, Inc. New Canaan, Connecticut.

- Beck JS, "Biomembranes: Fundamentals in relation to human biology." NY, NY McGraw-Hill 1980

- Enig MG, "Trans fatty acids in the food supply: A comprehensive report covering 60 years of research.", Enig Associates, Inc. Silver Springs, MD 1993

- Okolska G et al, "[Current recommendations concerning the rational use of fats. II. Value of polyunsaturated fatty acids from the n=6 and n=3 groups and general recommendations]. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig 1989;40(3):178-187

Return to home page